Mumbai: More than 300 people at work in every taluka, a high demand for Modi script translators, a prototype of how the word “Kunbi” can be written in different ways in different scripts and, in some cases, district level officials going village to village to map family trees.

This, in a nutshell, sums up what’s going on at the ground level as the Eknath Shinde-led Maharashtra government scrambles to complete the identification of all Marathas who once belonged to the Kunbi caste before the 2 January deadline for their quota.

Leaders of the Maratha community say that all Marathas have their roots in the agrarian Kunbi clan and should be given reservation in government jobs and education as Kunbis under the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category.

A separate quota for Marathas is embroiled in a court battle, with the Supreme Court having struck it down in 2021, calling it “unconstitutional”. The state government has filed a curative petition.

Maratha community activist Manoj Jarange Patil, who has been leading the latest wave of protests for a Maratha quota, has given the state government time until 2 January to identify all Marathas whose ancestors had Kunbi documents, and grant them the caste certificate.

“Because there is not much time, there is almost a competition going on between districts on who completes the exercise of identifying Kunbis faster. As a result, the whole process has gathered speed,” Ayush Prasad, district collector, Jalgaon, said to ThePrint.

He added that in every taluka, there are 300-400 government officials involved in the process of identifying Kunbis. “We have 15 talukas, so in our district about 4,500 people are involved in this activity,” he explained.

The Maharashtra government has directed all districts to scour different types of documents related to their regions — school records, land records, birth and death records, crime records and so on. The districts have to identify Kunbi references across these documents and publish them in the public domain.

Officials said the state government has given district offices the “deadline of 30 November” to complete this task.

Post that, people will be urged to go through these Kunbi references found, show the family genealogy and submit claims for caste certificates, officials across districts told ThePrint.

Also Read: Maharashtra’s Maratha quota stir puts Fadnavis in a tight spot, CM Shinde attempts damage control

Brittle documents

For almost all districts in Maharashtra, revenue records are fully digitised. But district officials have to scan much more than just revenue records, and in many cases the records are centuries-old brittle papers.

“They are old, torn and tattered and some crumble at the slightest touch,” said Deepa Mudhol Munde, collector of Beed district in the Marathwada region, while speaking to ThePrint.

She cited a few other challenges — no last names on records, records of siblings where one’s caste says Kunbi and the other’s says Maratha, and so on.

“The talathis (officer of revenue department at the taluka-level) are tallying records as and how we find them. If we find more records bunched in a particular village, the local talathi visits and literally draws family trees to ascertain the origin of families living in those villages and how they might be linked to the Kunbi records found in our documents. Those making Kunbi claims now are the fourth or fifth generation of the original Kunbi record-holder in their families,” Munde said, adding that her district had so far found 4,210 Kunbi records.

The next step, she said, is to set up camps in villages with a large number of Kunbi records for people to come forward with their Kunbi claims and genealogy, and grant caste certificates to entire families.

“For now, translating and displaying the documents is a big task,” she said.

The Jalgaon district gave an order for the purchase of regular scanners and fast scanners to quickly digitise Kunbi records found by staff and display them online. But officials soon found that the scanners were of little use. The documents were too old and the paper was too thin.

“We came up with an alternative. The talathis started scanning documents on their smartphone cameras. (But) this was turning out to be terrabytes of data and time-consuming to upload,” said Archana More, deputy collector of Jalgaon district, who is the point of contact for all tehsildars in the district.

The district then came up with another brainwave. Officials opened Gmail accounts in their names and purchased extra storage on Google Drive.

“Here too, there was a slight hiccup. The extra storage could only be purchased using credit cards and not everyone had them. So, we had to ask a few designated officials to make the purchase,” district collector Prasad said.

The Jalgaon district has searched 22 lakh records until now and found close to one lakh Kunbi references. However, some of these could be repetitions and will be weeded out, officials said.

Different scripts

District-level officials ThePrint spoke to also said the records that show Kunbi lineage are scattered across four different scripts depending on the time when they were created.

Some, dating back to the British era, are in the Roman script. Some, from the Nizam rule, are in Urdu. Many pre-1900 records are in the Modi script, while some recorded in the 1900s are in the Devanagari script.

So, the first thing that all district officials did was to arrange for Modi script readers and translators.

“We asked our Modi readers to give us all the possible ways in which the records might state that the identity of a person is Kunbi,” S. Salimath, district collector of Ahmednagar, told ThePrint.

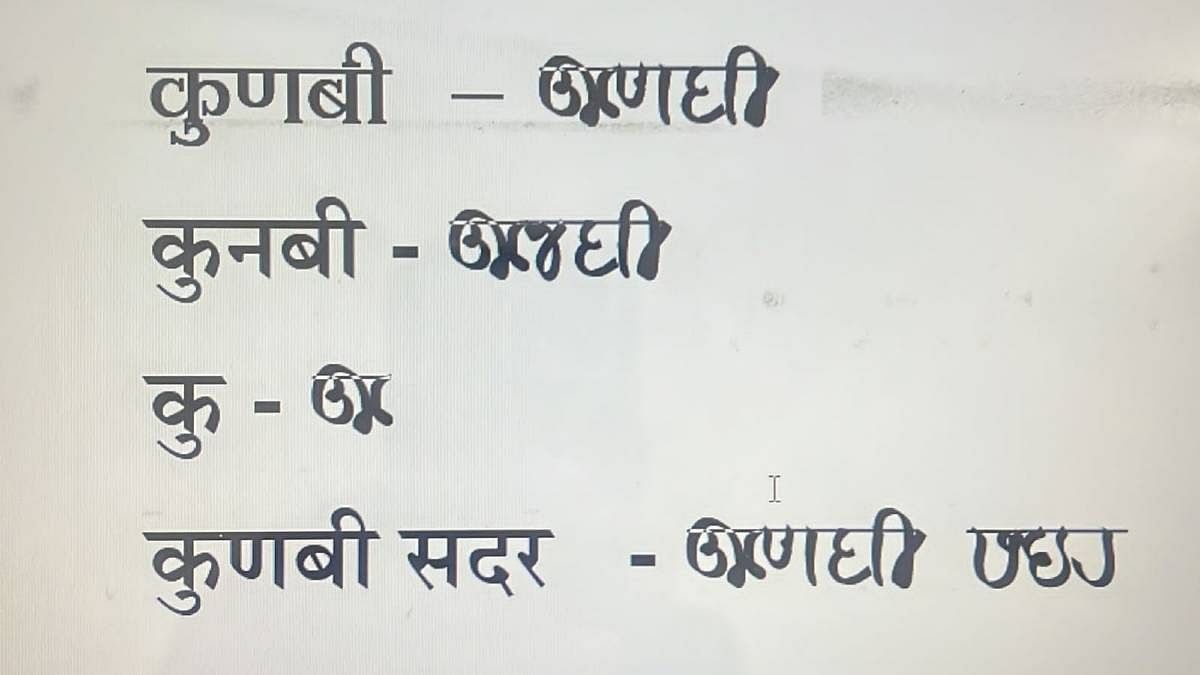

Several districts have adopted the same approach. According to the Modi translations that ThePrint has accessed, the word “Kunbi” is found in at least four different formats across documents.

“We gave this sample to all our employees going through pages and pages of government records. The ones that they prima facie flag as Kunbi, we send to our translator and then it is certified. The Modi script records are mostly those that were created prior to 1930. Post that, there are records in the Devanagari script,” Salimath said.

He added that the Ahmednagar district has already come across 60,000 Kunbi records.

Pune collector Rajesh Deshmukh said he had a slightly easier job. His district has allotted 32,000 Kunbi caste certificates in the last five years, so officials are familiar with the process.

“No doubt this is a mammoth task, but the system is already in place. We have already found 60-70 Modi script readers,” Deshmukh told ThePrint.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Victor in 2018, in shadows now — how Fadnavis shed political weight between two Maratha quota stirs