In early 1969, Ken and Dub, two music fans from Los Angeles, found themselves in possession of some unreleased Bob Dylan songs recorded in 1967 that had been sent as demos to his music publisher. Copies of the acetate recording spilled out among people working in the recorded music industry. Ken and Dub, both employees at a major record distributor, saw these songs as a lost Dylan album and saw a financial opportunity.

Using their connections, they found a record-pressing plant that would make copies. The result, a completely illegal and unauthorized album, was surreptitiously sold from the trunk of their cars under the title Great White Wonder.

By July 1969, the recording had spread all across North America and was even getting substantial radio airplay. The modern bootleg record had been born — and the recorded music industry had a brand new problem on its hands.

Bootlegs proliferated through the 1970s. Some originated from people working in recording studios. Others were dubbed from test pressings and cassettes that were meant for internal use. Enterprising bootleggers kept an eye on the dumpsters outside recording studios, waiting for someone to throw out used reels of audio tape, some of which contained unreleased gold at best and at worst, interesting audio documentation of the creation of an album.

Organizations representing the recorded music industry worked with law enforcement to clamp down on bootleggers but were faced with a global game of Whack-a-Mole. Production moved to countries where intellectual property laws were lax and law enforcement of such things was sketchy: China, Russia, Poland, Ukraine and Indonesia. Other territories — Italy, for example, along with tiny San Marino — had copyright laws where various types of bootlegging weren’t illegal at all under certain circumstances. Even in the U.K., live recordings that meet specific criteria are still considered legit. I never leave London without buying a few.

Criminal elements also got involved. It was said that the Irish Republican Army financed some of its terror campaigns through the sale of bootleg recordings. In the tri-border area of South America — the spot where the borders of Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay all come together and infamous for smuggling and organized crime — there was a steady trade in bootlegs and counterfeit records. Many made their way to the West, where they were sold from under the counter to special, trustworthy customers at independent record stores.

(Sidebar: Bootlegs are compilations of songs culled from different sources or unauthorized live recordings, although some acts, like the Grateful Dead, Pearl Jam and Metallica, encourage fans to make and trade their own recordings made at concerts. Counterfeit records are like counterfeit money: They’re designed to look like the real things in order to fool the consumer. Music fans tend to favour bootlegs because they offer material unavailable anywhere else.)

Bootlegging and counterfeiting continued into the CD era. Some labels, such as KTS (short for Kiss the Stone), became renowned for high-quality releases, issuing somewhere around 500 CDs by everyone from The Beatles to U2 to Nirvana. Kurt Glemser, a Canadian, released more than a dozen editions of a guide to bootlegs called Hot Wacks that became a bible to collectors.

When the internet hit in the middle ’90s, physical bootlegs went into decline. As people migrated to file-sharing, supply dried up. The last store I knew of that regularly and reliably stocked bootlegs disappeared about 15 years ago. Today, almost all bootlegs are digital and live on servers that have proven insidiously difficult to shut down.

Now there’s a new bootleg war. And it involves human voices.

The Recording Industry Association of America, the organization representing the interests of American labels, recently released its annual Notorious Markets List, which it submits to the U.S. Trade Representative in hopes that the American government will do something. It names countries that are either ignoring the theft of music or not doing enough to combat it.

In previous years, the RIAA has called out the usual suspects — Russia and China are always mentioned — but has also verbally spanked Canada for not doing enough to prevent the unauthorized copying and distribution of illegal recordings. We’re mentioned twice in this year’s report relating to hosting providers with homepages that redirect searches to sites in places like Luxembourg where such recordings can be found.

But this year, the Notorious Markets List cites a new problem: voice clones. I quote: “The year 2023 saw an eruption of unauthorized AI vocal clone services that infringe not only the rights of the artists whose voices are being cloned but also the rights of those that own the sound recordings in each underlying musical track. This has led to an explosion of unauthorized derivative works of our members’ sound recordings which harm sound recording artists and copyright owners.”

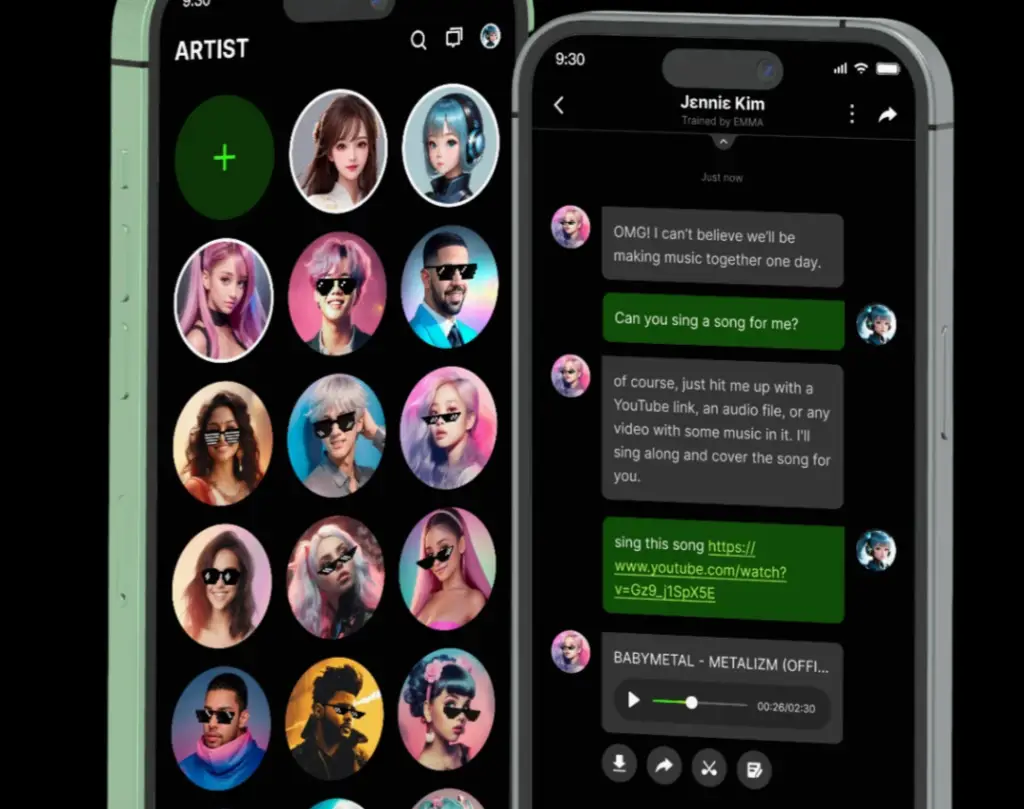

Only one site is mentioned by name: a cloning service designed by a 20-year-old computer science student in the U.K. Voicify.ai features vocal models of artists like Michael Jackson, Justin Bieber, Ariana Grande, Taylor Swift, Elvis Presley, Bruno Mars, Eminem, Harry Styles, Adele, Ed Sheeran and many others, including Donald Trump, Barack Obama and Joe Biden. Within seconds, anyone can have any one of these people say or sing anything you’d like.

I quote from the website: “Interactive chatting lets you converse with your celebrities as if they were your friends” and have them “(sing) covers of any songs you like, just to make you happy.” All you need is the app, which is available for both iOS and Android. The description reads: “YourArtist.AI app is one of the most popular and powerful AI music generator. It provides worldwide popular AI artist voices that sound human-like and realistic, enables anyone to produce AI music in seconds.”

But is this illegal? It’s unclear. The law has a lot of catching up to do when it comes to artificial intelligence. You would think that consent from the artist should be required, but there’s no uniform framework from country to country. In the U.K., there’s nothing preventing Voicify.ai from doing what it’s doing.

The RIAA is very annoyed and wants voice cloning to be classified the same as physical bootlegs, torrent sites, cyberlockers and stream-rippers. It says AI voice cloning has resulted in “an eruption of unauthorized AI vocal clone services that infringe not only the rights of the artists whose voices are being cloned but also the rights of those that own the sound recordings in each underlying musical track. This has led to an explosion of unauthorized derivative works of our members’ sound recordings which harm sound recording artists and copyright owners.”

The U.S. government seems to be listening. Just last week, a group of senators introduced a bill called the Nurture Originals, Foster Art, and Keep Entertainment Safe Act, otherwise known as the NOFAKES Act. It would “prevent a person from producing or distributing an unauthorized AI-generated replica of an individual to perform in an audiovisual or sound recording without the consent of the individual being replicated.” Those who violate the proposed law would be liable for the damages caused by the AI-generated fake.”

The law would also go after the platforms hosting the “unauthorized replication” and they would be held “liable for the damages caused by the AI-generated fake.” That’s pretty broad, taking in everything from sites like Voicify.ai to YouTube, Spotify and TikTok.

Voicify.ai is still in its early days but it’s spreading fast. Other such programs will follow. Don’t be surprised if you hear someone that sounds like Taylor Swift singing Hammer Smashed Face by Cannibal Corpse. Hey, I’d listen.