Editor’s Note: This article is a reprint. It was originally published April 10, 2019.

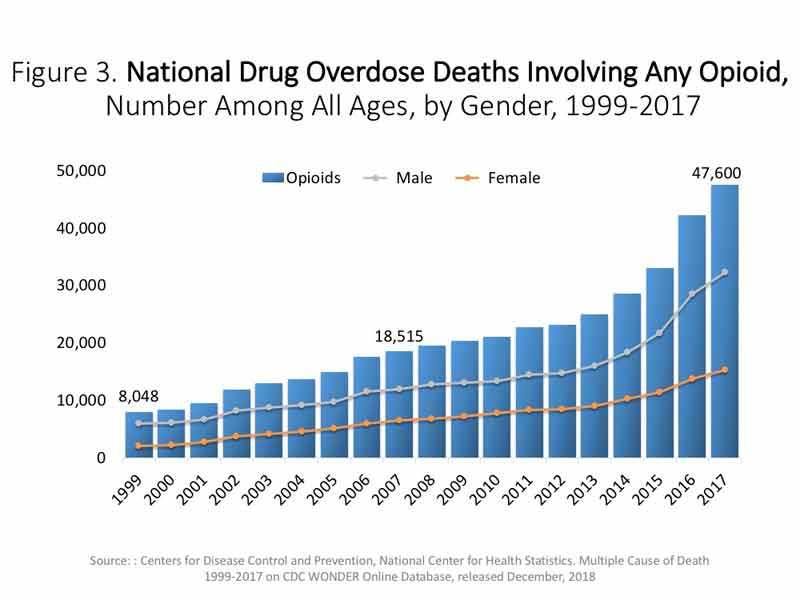

In November 2016 then-U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy reported that 78 Americans were dying every day from opioid overdoses — four times as many as in 1999.1 Requesting a nationwide call to action, Murthy asked the country to shift away from current policies and approach the problem as a clinical or public health issue, rather than a criminal one.2

As of June 2017, opioids had become the leading cause of death among Americans under the age of 50.3 The following graph by the National Institute on Drug Abuse shows the progressive incline in overdose deaths related to opioid pain relievers between 1999 and 2017.4

This does not include deaths from heroin addiction, which we now know is a common side effect of getting hooked on these powerful prescription narcotics. Indeed, prescription opioids have become the primary gateway drug to heroin5 and other illicit drug use, and prescription painkillers — not illicit drugs — are among the most commonly misused drugs in the U.S.6,7

False Advertising Created the Opioid Crisis

In previous articles, I’ve discussed the role false advertising played in the creation of this national disaster. To recap, a single paragraph in a 1980 letter to the editor (not a study) in the New England Journal of Medicine — which stated that narcotic addiction in patients with no history of addiction was very rare — became the basis of a drug marketing campaign that has since led to the death of hundreds of thousands of people.

In reality, opioids have a very high rate of addiction and have not been proven effective for long term use.8 According to The New England Journal of Medicine, opioids have not been proven safe or effective beyond six weeks of treatment, as most of the clinical trials with them have been less than that.9 “In fact, several studies have shown that use of opioids for chronic pain may actually worsen pain and functioning, possibly by potentiating pain perception,” the NEJM states.

The massive increase in opioid sales has been repeatedly blamed on an orchestrated marketing plan aimed at misinforming doctors about the addictive potential of these drugs. Purdue Pharma, owned by the Sackler family, was one of the most successful in this regard, driving sales of OxyContin up from $48 million in 1996 to $1.5 billion in 2002.10

Purdue’s sales representatives were extensively coached on how to downplay the drug’s addictive potential, claiming addiction occurred in less than 1% of patients being treated for pain.

Meanwhile, research11 shows addiction affects as many as 26% of those using opioids for chronic noncancer pain, and 1 in 550 patients on opioid therapy dies from opioid-related causes within 2.6 years of their first prescription.

In 2007, Purdue Pharma paid $634.5 million in fines for fraudulently misbranding OxyContin and suggesting it was less addictive and less abused than other painkillers.

The company was charged with using misleading sales tactics, minimizing risks and promoting it for uses for which it was not appropriately studied. More than a decade later, it’s become clear the company did not learn its lesson or change its deceptive and dangerous behavior.

Will Justice Catch Up With the Sackler Family?

In recent years, a number of states and municipalities have sued Purdue Pharma over the role it played in the opioid crisis. In March 2018, the company reached a $270 million settlement with Oklahoma, about $122.5 million of which are earmarked for the funding of a drug addiction treatment center at Oklahoma State University12 that will study opioid addiction and its treatment.13

About $12.5 million will be dispersed to local governments to address the opioid epidemic, while $60 million will cover the legal fees incurred, Reuters reported. As part of the deal, Purdue has also agreed to stricter limitations on how they market and sell opioids in Oklahoma.14

When you consider Purdue has made an estimated $35 billion from sales of OxyContin since its release in 1996, settlements of a few hundred million dollars is still akin to a slap on the wrist. Originally, Oklahoma had sought damages in excess of $20 billion.

According to Reuters, Purdue Pharma still faces some 2,000 other lawsuits,15 and in the face of this flood of legal action, Purdue’s chief executive has announced the company is considering filing for bankruptcy protection — a common tactic aimed at stemming the flow of lawsuits — and according to news reports, the possibility of bankruptcy was a significant factor in the company’s negotiations with Oklahoma.

The state wanted to strike a deal to ensure some form of compensation, even if it meant agreeing to a much lower amount. However, mere days later, Purdue was struck by another legal twist; this time by the state of New York, which alleges the company has fraudulently transferred funds into trusts and offshore accounts owned by members of the Sackler family in an effort to shield assets from litigation.16,17

Eight Sacklers Named in Expanded New York Lawsuit

As reported by Reuters:18

“New York Attorney General Letitia James made the claims in a revised lawsuit already pending against Purdue over its role in the opioid epidemic that added members of the Sackler family and other drug manufacturers and distributors as defendants …

In her lawsuit, James accused Purdue of seeking to ‘intimidate’ states pursuing lawsuits against it by threatening bankruptcy, which would hinder their cases and limit their ability to recover damages.

Yet James said Purdue, which is fighting lawsuits by 34 other states and hundreds of localities, has continued in the face of its liabilities to pay millions of dollars to the Sacklers. The lawsuit argued Purdue was either insolvent or near insolvency when it transferred those funds, making the transfers illegal under New York law.”

In all, eight Sackler members are now named as defendants in New York’s expanded lawsuit: Richard, Jonathan, Mortimer, Kathe, David, Beverly, Theresa and Ilene Sackler Lefcourt.19

The lawsuit seeks to return fraudulently transferred assets to the company and prevent the Sacklers from transferring assets to other entities so they don’t lose them in their eventual bankruptcy. It also seeks to strip all listed defendants of their drug licenses and bar them from marketing and distributing painkillers in New York until or unless they agree to abide by stricter rules.20

According to the complaint, pharmaceutical distributors, including Cardinal Health, McKesson, Amerisource Bergen and Rochester Drug, colluded with pharmacies to avoid raising red flags indicating drug misuse by warning the pharmacies when they were nearing their monthly opioid limit, and then manipulating the timing and volume of orders to get around the limits.

The complaint also charges Purdue with secretly setting up a new company, Rhodes Pharma, in 2007 while the company was being investigated by federal prosecutors, as a way to protect the Sacklers from the mounting OxyContin crisis and continue their profit scheme.21

Rhodes Pharma makes generic opioids, allowing the Sacklers to benefit from the opioid epidemic both in terms of brand name sales and generic sales.22 Between 2009 and 2016, Rhodes’ market share of opioid sales exceeded that of Purdue itself.23

Lawsuit Reveals Purdue’s Efforts to Maintain Profits

Rhodes Pharma and Richard Sackler also hold the patent to a new, faster-dissolving form of buprenorphine, a mild opioid drug used in the treatment of opioid addiction,24 allowing the Sacklers to further profit from the addiction crisis they helped instigate, the economic burden of which is costing the U.S. an estimated $504 billion a year.25

Indeed, according to a lawsuit filed in Massachusetts,26 Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers sought to increase opioid prescriptions while simultaneously developing overdose treatment to boost its profits.

The complaint quotes emails and internal documents alleging Kathe Sackler concluded opioid addicts were their next big business opportunity. Purdue identified eight ways the company’s experience in getting patients on opioids could now be used to sell treatment for addiction.27

Released unredacted files reveal Kathe Sackler’s involvement in “Project Tango” — a secret plan to shift the blame of addiction from opioid makers and distributors to the patients themselves.28

An article29 in The New York Times discusses Project Tango, noting that together, the two lawsuits by Massachusetts and New York “lay out the extensive involvement of a family that has largely escaped personal legal consequences for Purdue Pharma’s role in an epidemic that has led to hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths in the past two decades.”

Internal documents unearthed during these legal proceedings include charts and diagrams illustrating “the business potential of adding addiction treatment to the mix,” The New York Times writes. Such documents have led to members of the Sackler family being added to lawsuits against the company not only in New York and Massachusetts, but also in Connecticut, Rhode Island and Utah. As noted by The New York Times:30

“The suits are not only an effort to get at the Sacklers’ personal fortunes — estimated by Forbes to be $13 billion — but to expose the extent to which the Sacklers themselves have been calling the shots.

‘If these allegations against the Sacklers are proven to be correct, that could dramatically change the potential reach of where the litigation goes to collect funds on behalf of the cities and states that are so desperately trying to get money to deal with the opioid crisis,’ said Adam Zimmerman, an expert on complex litigation at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles …

Purdue temporarily abandoned plans to pursue Project Tango in 2014, but revived the idea two years later, this time pursuing a plan to sell naloxone, an overdose-reversing drug, according to the Massachusetts filing. A few months later, in December 2016, Richard, Jonathan and Mortimer Sackler discussed buying a company that used implantable drug pumps to treat opioid addiction.

In recent years, the Sacklers and their companies have been developing products for opioid and overdose treatment on various tracks.”

One of those tracks is Rhodes’ buprenorphine. In March 2019, the FDA granted fast-track status to injectable nalmefene hydrochloride developed by Purdue31 — a drug used for the emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose said to have a longer duration of effect than naloxone. Purdue Pharma has also contributed $3.4 million to a company working on the production of a low-cost naloxone nasal spray as a cheaper opioid overdose antidote.32

Purdue Has Recklessly Ignored Harm to Patients

The Massachusetts complaint goes on to allege the Sackler family discussed threats to their finances as data from long-term opioid use indicated danger to patients. Sales dropped and the staff recommended increasing the number of sales visits to doctors.

The company hired global consulting firm McKinsey & Company to recommend strategies to boost sales and polish the image of the company, in order to offset emotional messages from mothers whose children had overdosed.33

McKinsey allegedly urged Purdue to direct sales reps at the most prolific opioid prescribers, “because prescribers in the most prolific group wrote 25 times more OxyContin scripts than the less prolific prescribers.”34 This group of physicians were classified as “Super Core.” Purdue allegedly ordered sales reps to make visits to these prescribers every week.

The complaint claims that within the notes of the sales reps are recorded more than 1,000 visits to providers, in which the reps recommended pitching opioids to elderly patients with ailments such as arthritis. The complaint goes on to describe how the consulting firm recommended sales reps convince doctors to prescribe opioids:35

“McKinsey had reported to Purdue on opportunities to increase prescriptions by convincing doctors that opioids provide ‘freedom’ and ‘peace of mind’ and give patients ‘the best possible chance to live a full and active life.’ McKinsey also suggested sales ‘drivers’ based on the ideas that opioids reduce stress and make patients more optimistic and less isolated.”

In other words, Purdue appears to still be filling doctors’ heads with misinformation about opioids in order to drive sales, even as people are dying from overdoses in droves. I guess a shift to killing the elderly could help hide the massacre taking place, but just because someone is old does not make shortening their life any less heinous.

Struggling With Opioid Addiction? Please Seek Help

Regardless of the brand of opioid, it’s vitally important to realize they are extremely addictive drugs and not meant for long-term use for nonfatal conditions. Chemically, opioids are similar to heroin. If you wouldn’t consider shooting up heroin for a toothache or backache, seriously reconsider taking an opioid to relieve this type of pain.

The misconception that opioids are harmless pain relievers has killed hundreds of thousands, and destroyed the lives of countless more. In many cases you’ll be able to control pain without using medications.

In my previous article, “Billionaire Opioid Executive Stands to Make Millions More on Patent for Addiction Treatment,” I discuss several approaches — including nondrug remedies, dietary changes and bodywork interventions — that can be used separately or in combination to control pain, both acute and chronic.

If you’ve been on an opioid for more than two months, or if you find yourself taking a higher dosage, or taking the drug more often, you may already be addicted. Resources where you can find help include the following. You can also learn more in “How to Wean Off Opioids.”

- Your workplace Employee Assistance Program

- The Substance Abuse Mental Health Service Administration36 can be contacted 24 hours a day at 1-800-622-HELP