Assessment is a critical component of the teaching and learning process. However, assessment is more than just grading and is often misunderstood. In order to provide useful information to instructors and students about student achievement, it must be understood that student assessment is more than just a grade because it should link student performance to specific learning objectives. In higher education, there has been an over-reliance on administering summative assessments and simply assigning student grades, often with minimal to no feedback provided prior to the conclusion of the course.

Providing student feedback on an assessment, or any assignment, provides extensive value. As defined by Carless (2015), feedback is a dialogic process in which learners make sense of information from varied sources and use it to enhance the quality of their work or learning strategies. The purpose of feedback is to enable students to effectively change the quality of their work: “Feedback is a process whereby learners obtain information about their work in order to appreciate the similarities and differences between the appropriate standards for any given work, and the qualities of the work itself, in order to generate improved work (Molloy and Boud 2013, 6).”

Based on my classroom teaching experience, I believe that recognizing the importance of student feedback fosters active engagement and self-reflection in the student learning process. When feedback is focused, it helps students monitor their own learning, make course corrections throughout the process, choose best strategies, and ultimately, better understand the learning objectives.

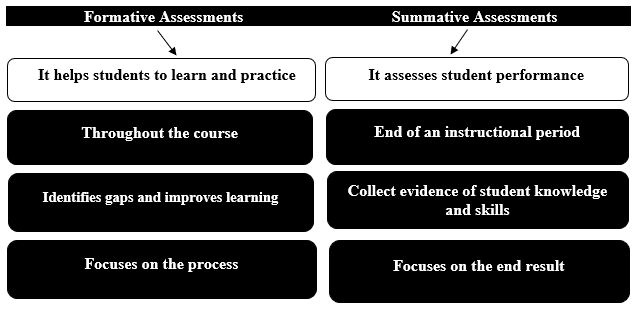

According to the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), the body for the accreditation of degree-granting higher education institutions in the southern states, the Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) evaluative framework consists of an assessment indicator. Within an institution’s QEP, the assessment plan indicator has to meet acceptable criteria according to SACSCOC. The expectation is for all Quality Enhancement Plans to include both formative and summative assessments. When developing our institution’s QEP, we had to ensure our assessments aligned with two main categories: formative, which describes tasks or skills that are in process or being formed, and summative, which evaluates the sum total of skills or comprehension achieved. Both types of assessments are used to identify levels of mastery and provide students and instructors with diagnostic information.

Below, in diagram 1, are some examples of formative and summative assessments that can be utilized in the classroom.

| Examples of Formative Assessments | Examples of Summative Assessments |

|---|---|

| Weekly quizzes | Multiple-choice/short-answer exams |

| In-class discussion | Oral presentations |

| Discussion board (Blackboard or Canvas) | Essays |

| One-minute papers | Research paper |

| Kahoot | Team projects |

| Poll Everywhere | Portfolios |

| Quizlet | Lab report |

| Muddiest point | Group exams |

| One-sentence summary | Prezi |

| Homework | Create a video |

| Jigsaw | Concept maps |

Formative assessment and feedback are fundamental aspects of learning. In higher education, both topics have received considerable attention in recent years with proponents linking assessment and feedback—and strategies for these—to educational, social, psychological, and employability benefits (Gaynor, 2020). On a practice and policy level, there is widespread agreement that formative assessment and feedback should be featured within course design and delivery (Carless & Winstone, 2019). There needs to be a clear distinction between when formative and summative assessments are primarily utilized. Diagram 2 below describes the distinction.

| Formative Assessment | Summative Assessment |

|---|---|

| Occurs frequently throughout instruction (e.g., during a unit of study) | Occurs after the instruction is complete (e.g., at the end of a unit of study) |

| Focuses on assessment for learning | Focuses on the assessment of learning |

| Informs ongoing instruction to improve student learning outcomes in real time | Evaluates how well the instruction worked in the past |

| Usually covers discrete content (e.g., one skill or concept) | Covers larger instructional units of study, such as a full semester or a year |

| Often uses qualitative (descriptive) data to evaluate a current state based on informal measurement | Often uses quantitative (numerical) data to apply formal measurements and evaluation techniques to determine outcomes |

If students have only summative assessments, they will miss the educational opportunities of feedback, and if they have only formative assessments, the grades may be inflated. Both types of assessments are essential to ensure effective learning. Formative assessments support the learning process, while summative assessments validate the appropriateness of formative assessment. For example, in diagram 3 below:

According to Stassen, traditional grading does not provide the level of detailed, specific information essential to link student performance with improvement. “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest (Stassen et al., 2001, pg. 6).” Instructors, therefore, must always remember that grading is an aspect of student assessment but does not constitute its totality. This is why a well-designed course will have a balance of formative and summative assessments. During our monthly QEP Professional Learning Community (PLCs) sessions, we are deliberate about creating a data-driven environment. In the PLCs, instructors include data to help them understand how their students are progressing, and identify patterns of achievement and deficiencies in the curriculum content.

As both formative and summative assessments have a distinct purpose, they are used simultaneously in educational settings. According to research 34 years ago, Sadler (1989) and Black & William (1989) state that understanding where the gap is in someone’s learning is pointless if nothing is done with this information, or if nothing is done to improve the student’s learning. Formative assessment requires educators to gather data about student learning during the learning process instead of at the end of it. By targeting areas that need work during the learning process, instructors can help students excel at a constant pace. Formative assessment is the only assessment that can offer real-time data needed for an instructor to impact student learning at that moment. For that reason, summative assessments report data too late because the ultimate goal of assessment is to evaluate the progress achieved toward a learning goal.

Assessments will always impact how students learn, their motivation to learn, and how teachers teach. In an effort to continually improve instruction, our Quality Enhancement Plan Professional Learning Community (PLC) has shifted our focus from “what was taught” to “what was learned.”

Dr. Dimple J. Martin is the director of the Quality Enhancement Plan at Miles College. Martin is a former early childhood education lecturer at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, a former assistant professor of early childhood education, and a faculty professional development coordinator at Miles College. She also has over 18 years of administrative K-5 Literacy Leadership.

Carless, D. (2015). Excellence in university assessment: Learning from award-winning practice. London: Routledge.

Carless, D., & Winstone, N. (2019). Designing effective feedback processes in higher education: A learning-focused approach. London, UK: Routledge.

Gaynor, J. W. (2020). Peer review in the classroom: Student perceptions, peer feedback quality and the role of assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(5), 758–775.

Hughes, Gwyneth, Holly Smith and Brian Creese (2015). ‘Not Seeing the Wood for the Trees: Developing a Feedback Analysis Tool to Explore Feed Forward in Modularised Programmes’, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 40, no. 8: 1079–94

McConlogue, Teresa (2020). Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education: A Guide for Teachers. UCL Press.

Molloy, Elizabeth and David Boud (2013). ‘Changing Conceptions of Feedback’. In Feedback in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding It and Doing It Well, edited by David Boud and Elizabeth Molloy, 11–33. London: Routledge.

Sadler, D. Royce (2010). ‘Beyond Feedback: Developing Student Capability in Complex Appraisal’, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 35, no. 5: 535–50

Stassen, M. L. A. (2001). Program-based review and assessment: Tools and techniques for program improvement. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts.

Thomas, Bastin, (2022). Building products and practices for educators to accelerate learning with Linways. Linways Technologies.